Despite those issues, they finished the $45 million project on schedule in July 2023, ready for MCC’s fall semester.

Originally built in 1968 with the most modern technology available at the time, the reimagined facility now features classroom, lab, faculty, and student spaces designed to replicate today’s work world and foster training for high-demand careers in skilled trades, technology, and manufacturing. The design also provides flexibility to adapt as the physical and digital worlds continue to converge.

Rather than construct a new facility, MCC chose to renovate the existing one-story, 110,000-square-foot building and add on 20,000 square feet of new space. Nearly $15 million of the project’s funding came from a capital outlay appropriation from the State of Michigan, with the remaining $30 million covered by MCC’s capital projects fund.

In order to transform the outdated structure, “Everything was gutted in the building; all that was left was the shell,” said Scott Schollenberger, Barton Malow’s General Manager, Education Group. “Openings changed because layouts changed, and they wanted to get everything back in-wall. We removed a lot of load-bearing masonry walls, so there was a ton of shoring throughout the entire project.”

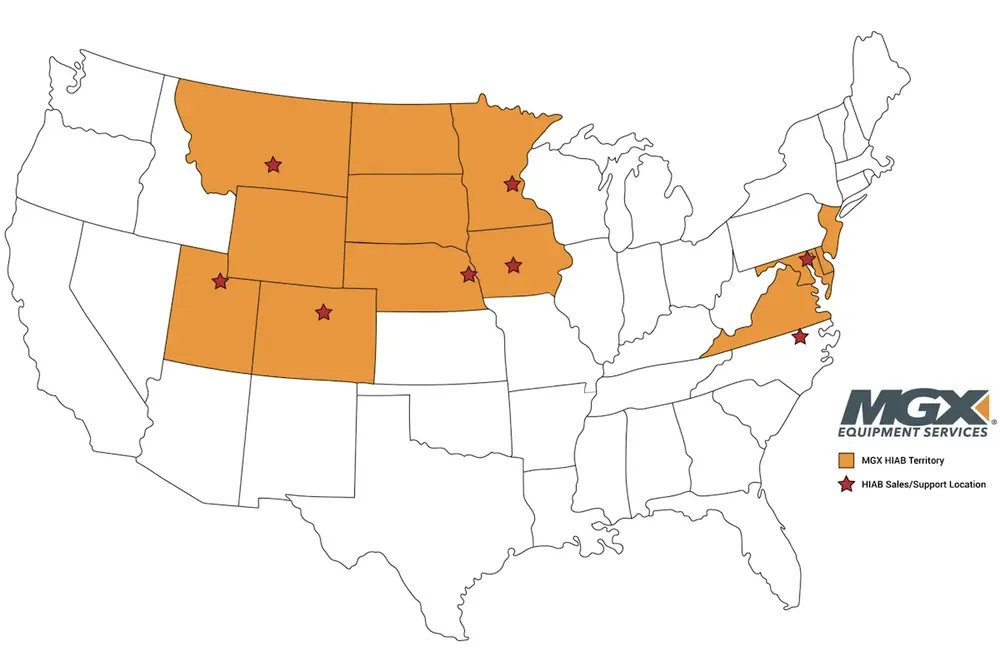

| Your local Trimble Construction Division dealer |

|---|

| SITECH Allegheny |

| SITECH Northeast |

That required extensive coordination to engineer the shoring so crews could demolish the existing concrete flooring, install new foundations, then install new masonry walls to support the structure.

In contrast, the building’s addition tied in relatively easily. “They reused most of the exterior walls and just cut a couple openings,” Schollenberger said.

The polished concrete floors throughout the existing structure required additional coordination, though.

“We didn’t want wire mold in a new building, so we had to rip up floors to run conduit over to walls and the floor boxes for teacher stations and desks,” Schollenberger said. “The floor was pretty cut up all throughout, so we needed to pour a ton of concrete.”

After demolition, “With the building being that old, I always like to video the storm and sanitary lines to make sure there are no issues,” Schollenberger said.

In this case, he found a big problem. “The original builder who put in all the sanitary lines pitched them the wrong way,” he said. “Literally, these lines were full of solid waste. The only way it drained was because it’s down almost 10 feet and the hydrostatic pressure pushed waste through the lines.”

To fix the problem, “We had to rip up the concrete floors longways through two-thirds of the original structure, dig down to replace all that sanitary line, and pitch it the correct way,” he said.

Luckily, the sanitary lines ran down the center of classrooms so replacing them didn’t require additional shoring. However, other hidden conditions led to design and construction changes.

At the building’s main entrance, “When we started demolition, we had large holes we needed to patch to re-support the existing steel,” Schollenberger said. “We had to go back to the structural steel engineer and make changes on the fly.”

When crews began replacing the building’s windows, they discovered the old frames were embedded in the masonry.

“The only way to put the new windows in was to cut those flush,” Schollenberger said. “We had to add brake metal that matched the color of the exterior windows around the window jambs.”

For instance, “All of our chilled water, steam, condensate, and domestic water came through tunnel piping from a power plant, and all that piping had to be replaced,” Schollenberger said. “It’s all larger pipe, between 10 and 14 inches. Our electrical substations were also below-grade in those tunnels.”

The tunnels run 800 feet from the Skilled Trades and Technology Center to the power plant, requiring a total of 4,000 linear feet of new piping on new stanchions. Small areaways inside the building’s two electrical rooms – both below grade at tunnel level – provide the only access.

“It’s very tight down there,” Schollenberger said.

To manage all the complexities, “We had to coordinate the electrician’s work in the electrical rooms with the pipe work,” he said. “We needed to get all that pipe demoed and removed as soon as possible, then load the tunnels full of new pipe and stanchions. After we loaded everything in, then we could finish off the electrical rooms.”

“Our hands were tied,” said Jeff Machota, Barton Malow’s Senior Superintendent. “The manufacturer said their suppliers weren’t getting materials and their hands were tied.”

When asked how they worked around the long delay, Machota laughed and said, “That was a lot of fun. A lot of temporary heat with a lot of propane tanks to keep the building warm and somewhat conditioned for the finishes. We even brought in temporary cooling units for some spaces because the air handlers weren’t all running until June.”

With the construction challenges now past, the transformed facility provides new spaces for training tomorrow’s workers. Modernized classrooms include a welding lab, video production studio, clay modeling classroom, and larger spaces for mechatronics and robotics development. Bright, inviting spaces with natural light replaced poorly lit, closed-in areas. The renovation even corrected the imbalance in restrooms that the 1968 construction primarily designated for men.

- Owner – Macomb Community College, Warren, Michigan

- Architect – Hobbs + Black Architects, Ann Arbor, Michigan

- Mechanical/Electrical Engineer – Peter Basso Associates, Troy, Michigan

- Civil Engineer – Spalding DeDecker, Rochester Hills, Michigan

- Construction Manager – Barton Malow Builders, Southfield, Michigan; Scott Schollenberger, General Manager, Education Group; Jeff Machota, Senior Superintendent

“With today’s growing workforce talent gap, preparing residents for highly skilled jobs in the region has never been more important,” James O. Sawyer IV, MCC’s President, said in a statement. “Macomb Community College is committed to connecting residents to jobs with futures that can sustain families, and to expanding the talent pipeline to local business and industry.”

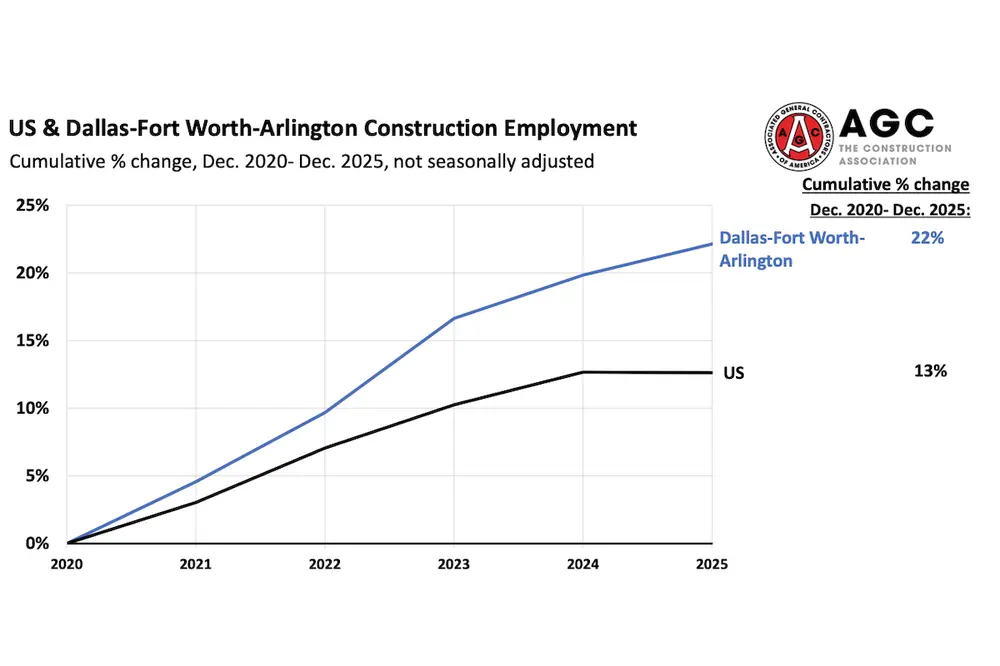

That could help ease the construction industry’s labor shortage.

“There aren’t a lot of people getting into the trades anymore; I think older guys like me are a dying breed,” Schollenberger said. “We need to let students know there are opportunities to get training, and not everybody has to get a B.A. I hope this new facility spurs interest for students.”

Photos courtesy of Barton Malow